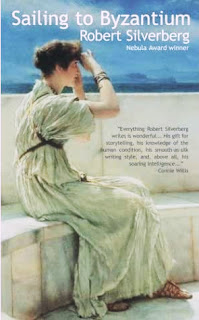

Some novellas deserve to be full novels, and Sailing to Byzantium is one of them. Robert Silverberg wrote this cross-genre jewel -- a mix of SF, fantasy, time travel, romance and mystery -- in 1984 and, deservedly, it won the Nebula Award.

In fact, the real mystery is why it hasn’t been filmed long before now, because it has the makings of a gloriously visual movie, especially in this age of CG effects, when the spectacular visuals (laid out in a narrative that must have been mind-bending in its day) can be brought to life in 3D.

The other mystery, equally confounding, is why Silverberg took an immense story that touches on so many subjects, and invested only a novella’s length in it. The plot is simple enough, to be sure; but the world he explores in a scant 40k words remains arresting almost forty years since the Hugo and Nebula were awarded. A novella, for this story? One wonders ... why?!

The other mystery, equally confounding, is why Silverberg took an immense story that touches on so many subjects, and invested only a novella’s length in it. The plot is simple enough, to be sure; but the world he explores in a scant 40k words remains arresting almost forty years since the Hugo and Nebula were awarded. A novella, for this story? One wonders ... why?!

In the fiftieth century, the world as we know it is gone (no surprise there), and the homogenized descendants of humanity are a comparative handful of functional immortals: physically perfect, they are masters of a magical technology which enables them to live as what one can only term ‘eternal tourists,‘ forever traveling from one fantastic city to another.

The rub is this: every city is a recreation of one of history’s great metropolises, raised from dust by legions of machines, permitted to exist for a short time then demolished, no doubt to be cannibalized for the materials to build another.

All the great cities of history are being recreated, five at a time (the limit is firmly imposed, no reason given, but one can hypothesize about the availability of materials, or the machinery that makes it all go). And the immortal citizens of the fiftieth century simply travel, party, enjoy, socialize, and generally have a great time among the grandeur and the teeming populations of ‘temporaries,’ who appear to be androids, possibly even hard-light holograms, all of them whisked into existence to complete the illusion of Alexandria, or Chang-An, or Constantinople itself.

Only a tiny percentage of the human population don’t enjoy the eternal lifestyle. One in a thousand, or perhaps ten thousand, still grow old. After an extended youth, when the aging comes upon them, they age rapidly. Such is Gioia, the lovely young thing with whom Charles Phillips falls in love. And Charles himself is the other, and even rarer, anomaly.

He’s a ‘visitor’ in the future: synthetic body and mind, machine-designed and built to bring the past to vibrant life for the entertainment (and perhaps the education) of the citizens, who -- by our standards -- often seem callow, and occasionally even moronic.

Charles isn’t the only visitor, but there’s barely a handful like him, constructs drawn from whatever century. Being synthetic, he’s a misfit, greater than the ‘temporaries’ but lesser than the citizens. Gioia is drawn to him as like is drawn to like: she also is a misfit, doomed to age with an incurable genetic condition.

When the rapid aging begins she flees, and as Charles literally pursues her around the world, city to city, he discovers what he is. Not a twentieth century man at all; not even a naturally-born human … something more, he decides, not less. Being synthetic, he's as timeless as the physically perfect (and intellectually somewhat dense) citizens; but what of Gioia, who is aging alarmingly. What can be done for her, amid this kaleidoscope of incredible technology?

The prose is stylish and rich and the world building tantalizing. If Sailing to Byzantium were double or triple the length, properly fleshed out and with the panoply of amazing concepts fully explored, it would make a novel today’s reader would deem awesome. At 40k words, it seems oddly abbreviated, in places thin to the point of anorexia. Silverberg has remarked on how the novella is a format he likes a great deal, and he clearly had a fine time here. But the material demanded, and deserved more.

Nebula and Hugo Awards notwithstanding, and as much as I adore Robert Silverberg, I want to give Sailing four stars rather than five, because it surely needed more growth, more investment, just more, to work truly brilliantly. It might have read better in 1984. Current readers -- in this age of hundred-episode sagas on tv and book series running many thousands of pages -- are seldom satisfied when thematic material is underdone. Sailing has a ‘rare’ quality, perfect on the outside but a tad too pink in the middle to suit all tastes. Which isn’t to say I don’t love this story -- I do! But my imagination runs away on flights of creative fantasy, filling in the blanks and building the sumptuous, thick novel I wish Robert Silverberg has written.

No comments:

Post a Comment