Friday, February 4, 2022

In the Company of Ghosts

Foolish, I suppose, to sit among my ghosts, but they’re my ghosts and I cherish them. Woodsmoke loiters on the still evening air, prickling into a hundred memories. Leaves drift softly from sycamore and chestnut, littering the path which wanders among headstones so old, many are worn smooth, relinquishing any hint of who lies beneath.

My bench sits under a skeletal oak. I’ve been still so long, the red squirrel returns, scampering over those anonymous stones and into the branches above me, in search of a last few acorns. The year is winding gently down; one can almost smell winter. The old graveyard will slumber, wrapped in a blanket of snow before long.

Like the squirrel, I came here searching, but he’s luckier. Acorns are plentiful while the stone I sought eluded me, and I must go soon.

October nights fall early and cold -- a chill discovered my toes an hour ago. My squirrel friend rushes home with his hoard and I, stiff after sitting too long with my ghosts, crunch away through drifted leaves.

He’s here somewhere, quite close, I think: the grandfather who showed me the world, taught how it wags, before he left it when I was still a child. My own days are as short as October’s. The end gnaws inside me, never far from my mind. This is my last October, so I wrap myself in it, as if it were a cloak. My squirrel busily plans ahead for spring, while I wind down with the year, settle to sleep like these trees.

The path takes me back to tall iron gates I’d forgotten; it’s been so long since I was here. Lights shine from the little church, and from houses across the way. A sweetness of stewing fruit wafts from one of them, reminding me of the season, and my ghosts creep closer, invited.

Harvest festival and jarring jam; turnip -- not pumpkin, not here, not then! -- lanterns for Halloween; the newsagents’ shop stocked with sharp-smelling fireworks for Bonfire Night; gathering twigs for the hearth on chill, bright afternoons exactly like this one, half a century ago. I recall the sound and feel of muddy boots crunching through russet, gold and amber, while keen winds stirred bare branches against windswept skies promising snow and, so soon, Christmas lights. Fun for the child, magic for me now. October magic.

My search for that one headstone was fruitless but the evening was far from wasted. Odd, how congenial the company of ghosts can be.

The sun is long gone as I walk away. The old town lies placid with evening, the sky clear, dark velvet. A few people, dressed for the cold, too busy to notice me, rush home like the squirrel -- and so must I, though I’m half a world away from home and won’t, can’t, return here.

So I pause, steal a few more moments to inscribe new-old memories into the crannies of my mind: the deepening calm of the fast-expiring year, the softness of trees settling to drowse until spring; a quiet and welcome I hadn’t looked for in this of all places, under the diamond sparkle of October stars.

Poem: Ode to a Black Cat

Master of the wide-eyed stare ...

Silken; soft -- with sickles, ten:

Will he shred? The question's when?!

Curled in slumber in his lair --

My pillows and his long-shed hair...

Five minutes on my lap and then

Without a glance he's gone again.

Thursday, January 27, 2022

Bloodlines

|

| The Pier Hotel and Landseer Building, Milang |

|

| Cattle country on the shore of Lake Alexandrina. |

|

| Milang Station, end of an extinct line and now a standing exhibit. In winter or early spring it's green. |

|

| The Narrung road -- in November, almost summer. Far side of Lake Alexandrina. |

|

| Narrung car ferry. |

|

| Gateway to the town of Raukkan. |

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Essay: A Milestone

There's a first time for everything, and although I've been published several times, and also at professional level, appearing in a very major magazine with full-on distribution is -- to me! -- an achievement, and a thrill. The contributor's copies of ANALOG Jan/Feb 2022 arrived yesterday, and how sweet it was to have it in my hand and chart this moment. The first step on a road which, I hope, will lead eventually to me marking a day, when I'm cradling a novel in both hands and making another milestone!

I did report the date when ANALOG accepted the story (before the launch of this blog, so it was marked on my personal blog, here on Dec 20, 2020); and also posted my news when the issue was released a couple of weeks ago (here) -- but this is quite different. Actually having the magazine in my hands makes it ... real.

It's also an inspiration to me, to be creative, keep driving forward. I do have stories to tell, and if one is completely honest, it can be a lot of fun telling them. I'd also like to write about writing, and in coming weeks and months I'll indulge myself here; but not at the moment when, after an absence of months, the muse has finally deigned to whisper into my ear. I'm hoping to complete a third story in as many weeks.

Updating this a little while later -- let's call that four stories in four weeks, and am about to start another! Eden Can Wait worked out well, though it came in at about twice the length I'd hoped for (about 10k, which will certainly make it harder to sell). However, A Marriage of Inconvenience came in at 3.5k, as did Dust Gets in Your Eyes, and from what I've come to understand about short story writing, this is close to the perfect length ... at least as far as editors understand it!

Writers might have a different view. For myself, I find it very much more difficult writing a coherent short story than writing a novel. This might sound odd, given that there's twenty times more work (no exaggeration) in a novel than in a short story, but trying to cut a story to fit into a 2,000 - 10,000 word window is ... agony. It's pure torture, which simply means I'm not a natural short story writer. Right.

Still, one perseveres -- and its also true that some story ideas will actually fall apart if they're treated at greater length. In fact, the story I'm about to write this afternoon is one of these ... so, time to get busy!

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Poem: How the Garden Sings

Thursday, January 13, 2022

North Wind (Thinking through my fingertips)

Bragutai was wild born, in the years when Eldric, Prince of the Feyn, still tried in vain to grow a man’s beard — when his sister, Zamarah, grew taller, shot straighter, swung an axe truer than their father’s favourite. It was Zamarah, not Eldric, who found Bragutai, no more than a bundle of bony legs, shivering beside his mother’s body when snows returned, far too late in the season … Zamarah who carried him home, fed him with her own hands, nurtured him, until he grew taller, stronger than the sires of the king’s best racers.

Save for custom, she would have ridden him to war, but the traditions of a hundred generations of the Feyn forbade girls to bear arms in battle. Many years of war had taught them that young women are the key to the future of any people, and must be shielded, not squandered, at least until their duty to the people is done, and the next generation half-grown to replace them.

So, it fell to Eldric to bear King Andregar’s colours into battle against the seething hoards of the Veru, savage tribes from the west who poured across the hills like tidal waves and offered no quarter. By now a young man, Eldric carried his father’s sword: time had caught up Andregar, leaving the old king trembling in his limbs, wandering in his thoughts, so frail that Princess Zamarah sat in his place upon the Kestrel Throne of the Feyn, and the chieftains took her counsel.

Two things only could Zamarah do for her brother, as he girded on his swords and laced his armour. She gave to him Olnar, the storm witch whose family — for their poverty and debt — were indentured to the Feyn royal house a decade before the boy’s birth. Olnar grew up with the gift of Sight. Wasted in the olive groves and kitchens, he spent his youth at the feet of Feynafell’s greatest mages, mastering every skerrick of magic they could teach while he learned how to command his gift, lest it destroy him as wildfire races through the forest.

And on the eve before battle, Zamarah sent for Eldric, and into his hand placed Bragutai’s halter. She trusted no horse before him. Twice, he saved her life when she was still only a girl — fought and defeated a mountain krall with fangs like scythes, and carried the young princess through a brawling river, when the bridge on the Tane collapsed. No magic or prayer could keep Eldric off the battlefield, for the Veru were starving at winter's end, as always. The instinct for survival spurred them east into gentler, more fecund lands than their own. But if any force could bring Eldric home, Zamarah placed her faith not in her father’s careless gods, who seemed deaf even to the entreaties of their own priests, but in Bragutai.

She watched from the revetment above Feynafell until her people’s battle colours faded from sight. Everything she held most dear marched beneath those banners, and she would receive no word until couriers raced home with news. Only Olnar could send messages, and then merely through the wyrd dreams which haunted Zamarah through the late spring and into the summer…

The winds swung southeast and warmed; spring rain fell as the new year’s crops were seeded; new foals romped and kicked in the paddocks where Andregar’s best stock were bred. She watched Bragutai’s progeny born in those months, while she fretted through the nights, her dreams filled with images of battle, hardship, danger and the longing for home. She might have wondered which dreams were Olnar’s and which were pure fancy, but instinct always told her the truth.

She knew when the Feynafell regiments were routed and sent scrambling for cover among the passes; she saw when fire overtook their supply column, and men went hungry while they cut the dogs loose to hunt for themselves and the horses made do with the high hills’ sparse graze. Zamarah knew when a spearpoint found Olnar’s leg, and he thrashed for days in delirium, wondering if it would be gone when he woke — and she also glimpsed the battle when the Feynaell regiment overrode the Veru, drove them northwest. They fell back, broken for the season just as the caribou returned to their hills and the hunting paths opened.

But Olnar had warned many times, victory would not be won without great cost; the butcher’s bill must be paid. The last battle soon shattered into a desperate scramble for the high ground, and though Eldric’s lieutenants — the chieftains Gareth and Weyland — wrought victory out of chaos, Eldric found himself cut off from the regiment. Wounded, he beat a path through crags and high timber where the Veru and the sickle-fanged krall could smell blood on the air.

Messages of victory sped to Feynafell with regimental couriers, ahead of the wagons bearing the wounded, but the force remained in the north, searching the passes for Eldric. In a week, even Gareth and Weyland gave him up for dead. Only Olnar continued to swear that Eldric lived and was at liberty, though even he could not find the prince in the tangle of rock and heather, where the high hills became the low slopes of the Alcaus Mountains.

In a month, only a token force remained at Trolldance Rocks, and that because Olnar refused to leave. The young witch wrote to Zamarah, swearing on his gods that he could feel Eldric in the wild. Placing her faith in her childhood friend, and with the Veru danger spent now, Zamarah took a party of scouts and lancers and hurried north from Feynafell.

At sunset, when the krall began to wail over the high valleys, they came upon the camp in the wind-shadow of the high granite outcrop known as Trolldance Rocks. Olnar’s wound had healed well enough for him to ride, and at dawn they went out, following his fey instincts … but it was Bragutai who brought Eldric back — both of them wounded, at the end of their strength.

Eldric would recover, with the finest surgeons the old king could provide, but Bragutai’s race was run, and the horse knew it. He had become a legend already, and would never be forgotten — the people of Feynafell tell his story still. Zamarah sang his elegy as he was honoured the way all great horses are: his head, his heart and his hooves were buried deep, where the krall would not find them, among purple heather on a wild hillside not a mile from where he was born.

Announcement: The Way Back is published in ANALOG Jan - Feb 2022

Brilliant news: The Way Back has been published in the January - February 2022 issue of ANALOG. This is a great thrill for me, since I've been reading this magazine for decades, and it's the SF market leader.

Here's the link to the current issue ... please note that after February 2022, this link won't work: it's specifically for the current issue. Newsstand magazines really are "ephemera;" when they're off the stands, no longer current, one falls back on used copies, which change hands on eBay, Amazon and so forth. And for those, I can't provide a link. Alas, the ANALOG site has no store where you can buy specific back issues. They sell subscriptions, not copies, and the same is true of Amazon. If you're ordering before the end of February, 2022, however, that sub should include the issue in which The Way Back appears.

Announcement: Vector is online, at Dark Recesses Press

I'm rather late with this announcement ... Christmas, New Year, the holiday season, the hot Aussie summer -- blame one and all. But, somewhat belatedly, it's my great pleasure to announce that Vector has gone online at Dark Recesses Press ...

It's an offbeat little tale of a cat, a litterbox, a new brand of cat-litter, and something perfectly ghastly afoot. A five minute quick-read, and if you enjoy a shiver...

Sunday, January 2, 2022

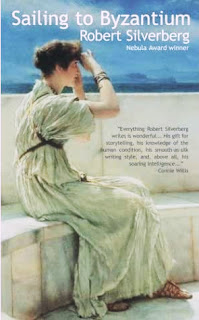

Review: Sailing to Byzantium

Some novellas deserve to be full novels, and Sailing to Byzantium is one of them. Robert Silverberg wrote this cross-genre jewel -- a mix of SF, fantasy, time travel, romance and mystery -- in 1984 and, deservedly, it won the Nebula Award.

The other mystery, equally confounding, is why Silverberg took an immense story that touches on so many subjects, and invested only a novella’s length in it. The plot is simple enough, to be sure; but the world he explores in a scant 40k words remains arresting almost forty years since the Hugo and Nebula were awarded. A novella, for this story? One wonders ... why?!

-

The invitation must have been delivered in the morning, though Rick Stewart had no idea how it found its way onto the phone table in the h...

-

It's my great pleasure to announce that "Islands Of the Mind has recently appeared in Way of Worlds , a science fiction anthology...

-

What a great pleasure to be able to report that Falling will be appearing in ANALOG Science Fiction, probably some time in 2026. This one w...